(Ed. note: This is the second part of a three-part blog on Siebert’s recent trip to Botswana. Read part one of her journey here)

LINYANTI WILDLIFE RESERVE, BOTSWANA – WEDNESDAY 8 JUNE, DAY THREE

Segomsee Oja, my guide from DumaTau, meets me at Chobe Air Strip, inheriting me from Savusati guide Keith Wasimona, who’s delivered two days of exhilarating bush adventures. I’m sad to say goodbye. But it’s a new day, a new vehicle, and a new destination – the Wilderness camp I’ve most longed to visit, recently listed on Conde Nast Traveler’s Hot List.

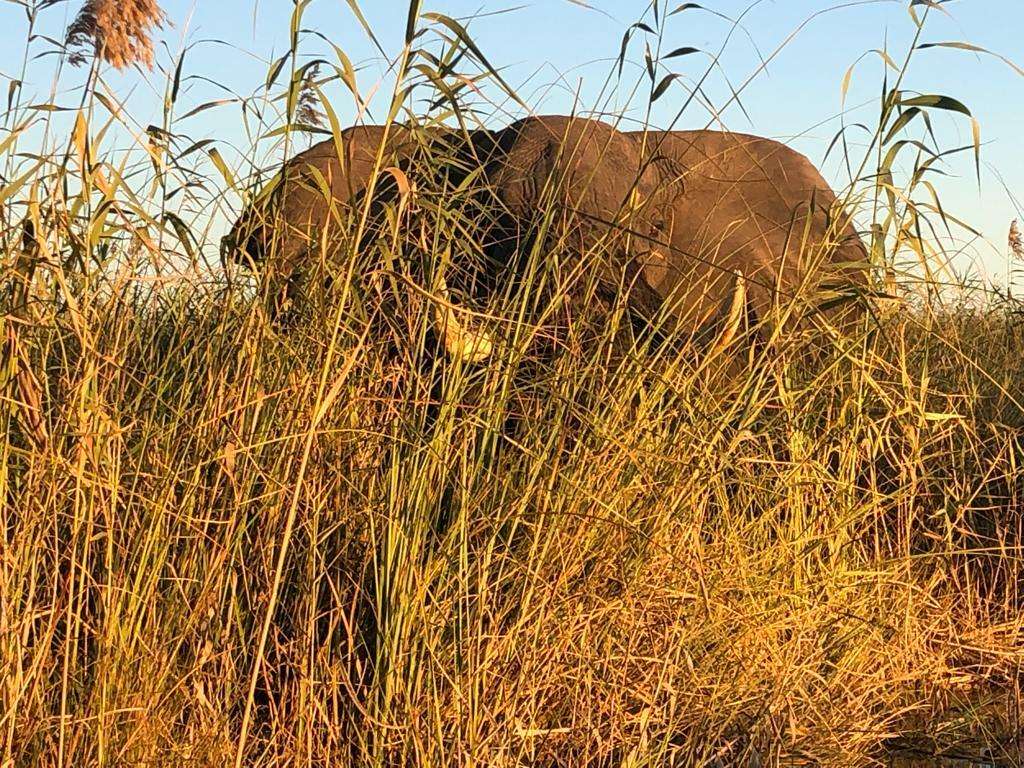

DumaTau. Roar of the lion. Though it’s the elephants I’ve mostly come for.

The Linyanti Wildlife Reserve is home to wildlife corridors traversed by the world’s largest elephant herds – and DumaTau lies between two of them. So when See asks, leaving the airstrip behind in the dust, what I’m most interested in, the answer is simple: Elephant corridors. Elephants.

As the winter sun warms up the day, we are back on a white sand track, like those Keith and I explored. Heading northwest this time, towards DumaTau, game viewing en route. I’ve got roughly 40 minutes to learn more about See. Because, in truth, I am more interested in people than animals, though especially partial to people who love animals. This I’ll soon discover: a former videographer, he’s playful, laughs easily, loves saying ‘true that’, has encyclopaedic knowledge about the Savuti Channel and much else, and remains unflappable in the face of giant bull elephants.

Perhaps his ease with elephants comes from growing up with them. In the Okavango village of Eretsha, one of the five villages of the Okavango Community Trust, Wilderness’ community partner in the Delta. Eretsha had no school, so See and his classmates walked seven kilometres to and from school in Beetsha – often meeting elephants along the way. Not always uneventfully.

‘Some days we encountered elephants on the way to school, especially during the flood season’, See says. ‘We had whistles to scare them off. Sometimes it worked, other times they would chase us. At first I was always scared, but then I got used to it. I realised that there is a comfort zone that you have to maintain to be safe from an elephant – about 300 metres away. If we met them around a corner, we’d run back to maintain a safe distance’.

Eventually a group of tourism operators bought buses to transport the schoolchildren, and these encounters ended. By that time See knew what he wanted to do with his life.

‘I was a wilderness kid’, he says. ‘Growing up I knew I’d be a guide’.

See has worked for Wilderness since 2013, starting as an escort guide, checking to make sure the guides didn’t go off road too much, and went off road responsibly. Then he was a Wow Co-ordinator, organising special activities at Mombo and Vumbura Plains. He arrived at DumaTau in 2020 to do guide training for two years, and that’s home now.

‘Guiding for me was translating what I learned as a child into English’, See says. ‘That’s how easy it was’.

As we drive past small waterholes frequented by impala, herons, hippos and other creatures, the scent of wild sage permeates the air.

‘Wild sage was used by hunters’, See tells me. ‘They would crush the leaves and rub them over themselves to disguise their scent from game. The stems are used to make fishing traps.

‘In the twentieth century, people still lived here. Pastoralists. They moved around and took their homes, the poles, wood, and grass thatch, with them. My family still lives in houses like that…my 32 siblings, all from Dad’.

Heeding my interests, See tells me about the elephant corridors: ‘You’ll see them from the boat…one on the east of DumaTau, one on the west’. Then as if on cue, we come upon an elephant skull on the roadside, bleached white with insides like a honeycomb.

‘This one died of starvation’, See says. ‘Though Linyanti elephants tend to live longer than other elephants, up to about 60 years. Because of their soft diet, the roots of waterlilies – it doesn’t wear their teeth down so fast.

‘During their lifetime, elephants get six sets of molars; each one lasts about ten years, with one set wearing out as another comes in. That’s why ellies die, usually, their teeth wear out and they starve’.

We reach camp, with another waving Wilderness welcome committee on the steps, leading the way into DumaTau’s third incarnation. First impression: wow, wow, and more wow.

It has an almost marine feel, open, airy, and elevated, with nautical rope balustrades and sweeping canvas overhead, wooden decking and views that don’t stop, out over the Osprey Lagoon, part of the Linyanti River. Its vastness reminds me of the Zambezi, or the Nile. These waters have come from Angola, through Namibia, to get here; they ebb and flow through the seasons, and shift according to fault lines below. They beckon.

First, though, a to-die-for delicious, fresh, plant-based lunch– harissa chakalaka cauliflower bowl – accompanied by traditional Batswana food morsels (ditloo falafel balls, morogo greens, indigenous tabbouleh, etc.)

It’s hard not to sing the camp’s praises. What’s great about DumaTau is the diversity – you can do game drives, night drives, fishing, boating, go on helicopter rides, nature walks…

I’m led down the elevated walkway to my room. My suite, rather – bigger than the cottage I rent in Cape Town. In earthy and sunset colours, there’s a lounge/bar; hallway (good for jogging); bedroom and deck with plunge pool and double day bed, sheltered by a sail like canvas and overlooking the lagoon; dressing area and bathroom; indoor and outdoor showers. I take a shower outside. Explore further – including lots of info about ellies and wild dogs framed on the walls. Rest a little. Can’t I just stay here?

No. I’ve made a plan with See to go out on the delta boat for the afternoon, and sundowners. When I meet him in the lounge again I ask him if it’s still the plan, if he’s ready to go boating.

‘I was born ready’.

So off we go, down to the jetty and onto the river, headed into the Zibadianja Lagoon. We pass ellies and more ellies, tearing up waterlilies and chowing their rhizomes. See shares more of his seemingly endless font of knowledge.

‘Elephants are perfect swimmers’, he says. ‘Except when very young. A baby elephant was taken just there recently by a croc as the herd was crossing the water’.

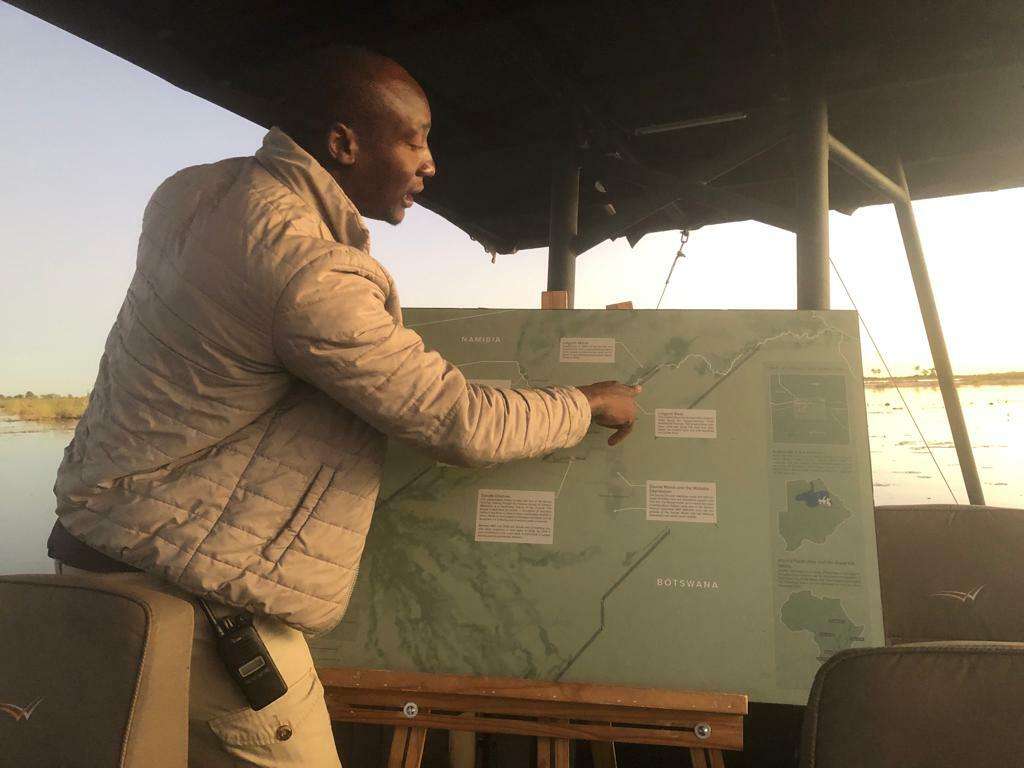

That said, being out on the water is incredibly peaceful. No one else in sight. Just the ellies, red lechwe leaping through the grasses, a croc or two submerged, jacana seeming to walk on water. See shows me the eastern wildlife corridor, a modest patch of sand, imprinted with elephant spoor, tracking into the bush. Certainly not the highway I’d envisioned. But critical to the elephant population for dispersal, as well as to others using the corridors – such as African wild dog.

See talks about the flow of water, the backflow of Namibia’s Kwando River, which becomes the Osprey Lagoon, about eight metres deep now and going to get deeper with the rains in the Angolan highlands, which feed into the Kwando. ‘We expect the water to come down from Angola soon’, he says. ‘It’s channelled by a fault line’.

He points out grasses used for thatch; floating islands that filter the water; more red lechwe. ‘Water is their safety net…they run into water when they sense danger’. We see a solitary hippo, and his pod 30 metres away.

‘He’s a loser’, See says. ‘Probably kicked out of his pod. Competition over females might be the cause. If one male doesn’t surrender, they might fight to the death’. More hippo info: ‘They can hold their breath underwater for six minutes by decreasing their pulse rate. They don’t have sweat glands so have to stay in the water to regulate their body temperature’.

The delta boat keeps catching waterlilies in its engine; we repeatedly slow down, or stop, so See can remove them. Finally, he turns off the engine and takes two waterlilies out of the water, one white, one yellow.

‘The white ones open up by day and are fertilised by bees, the yellow ones open up by night and are fertilised by birds’. Who knew? I feel like a child, discovering again. See makes me a necklace out of the lilies – and then fashions a hat for himself from a lily leaf, like the local fishermen used to wear. The lily rhizome stems can be used as a straw. He demonstrates.

In the distance, as the sun falls blazing orange-red, the black silhouettes of palm trees etch the horizon, the border with Namibia. Trees seeded by elephants, See tells me. Another ancient elephant crossing. It’s fantastical – here on this little boat, surrounded by elephants and other creatures, water everywhere, just the sound of the reed frogs chiming. The most gorgeous sunset I’ve ever seen. If it’s a dream, I don’t want to wake.

THURSDAY, DAY FOUR

The next morning we head out early towards the eastern side of the private concession, driving along the river. We see darters, jacanas, and kingfishers, more red lechwe among the banks of papyrus. See shows me a tree with mesh around the trunk: elephant proofing. Trees and elephants often don’t mix.

‘It’s been stripped by elephant. They eat the second layer, the layer with all the nutrients. The bark is rich in fibre so it boosts their digestive systems. If they ring bark a tree, stripping it all the way around, it kills the tree’.

That said, he continues, ‘Elephants play a vital role in the ecosystem. Impala like open areas, for instance, and elephants clear the way’.

You don’t go far in the Linyanti, at least at this time of year, without running into elephants. We come across a small breeding herd; it doesn’t take the matriarch long to spot us. Ears flapping, she breaks out of a grove of trees and runs towards us. We back off.

Less than half an hour later, we’re having a showdown with an old bull elephant on the road, thick vegetation on both sides and the river a stone’s throw to the left. He stares at us; See tries to nudge him backwards by advancing slowly. The bull retreats a few paces but then walks forward again, keeping his eyes on us.

‘Seriously?!’ See is not impressed.

It’s a tango, forward and back and forward again, to the side. The bull stops and stares, starts scratching himself on a tree, hides behind the tree and peers at us. Finally, after roughly thirty minutes, he turns and lumbers off in a cloud of dust and golden light.

I wasn’t afraid (I’ve been charged by an elephant before), but I ask See if guests often get scared in a face-off like this.

‘Yes. We look at the guest’s comfortability. We look in their eyes for fear. If there’s no smile, we don’t move forward’.

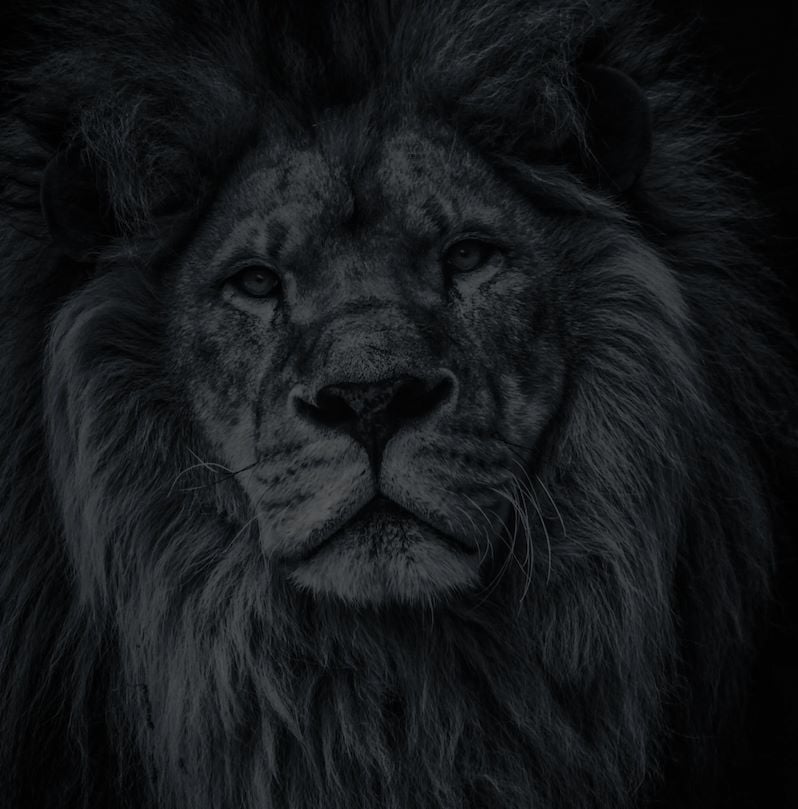

Talk turns to lions. There are currently four prides around DumaTau, See says – including a pride of five females that recently killed one of the local African wild dogs and her pups. Right now there are only three wild dogs left in the area. But it’s a movable feast, you might say.

We drive on, and see a business of mongooses scattering off into the bush, then a journey of giraffe and a zebra herd (See talks about mutualism between species, how they help each other). Elephants trumpet in the distance, which See interprets: ‘Maybe two herds meeting each other, like gangs’.

I feel like a child again, with this succession of wonders. See is equally delighted. ‘When you are in nature you are never bored. You are always discovering’.

As we head back to camp, he teases me with mention of ‘a surprise’. I hope he’s going to dance a traditional dance for me; I’ve heard he’s astounding. But that’s not it; we’re taking to the water again, this time on the camp barge – a lazy lunch as we drift along, of various pastas, grilled chicken breasts, salads, and a full bar. Elephants, of course, make an appearance on the banks and in the water.

‘Botswana is a paradise for elephant’, says See as we watch a huge bull, seeming to gaze at his reflection. ‘It’s like being in a swimming pool with a buffet right here. No one’s bothering them’. And adding a coda: ‘Ellies communicate through their feet, feeling the vibrations’.

Before an afternoon siesta, See asks me what I want to do later. He doesn’t have to ask. Grab the delta boat and go out on the water again.

We repeat yesterday’s pattern, but no day is ever the same in the wild. Out on the lagoon we see a white-necked otter diving for fish; See is thrilled. We see the ‘loser’ hippo again, still on his own, and as before ellies ripping up waterlilies and devouring them.

Then two startling scenes in a row: an elephant trailing a train of waterlilies like a king’s cloak, with jacanas along for the ride, followed by another elephant diving and resurfacing like a dolphin. See says he’s never seen anything like either before.

He mixes me a mean G & T, and then hauls out a board with text and graphics explaining the mysterious shifting waterways around us here in the Linyanti and south in the Okavango. How tectonic plates impact their flow, along with rainfall of course. It’s a labyrinth of information, I try to understand. But honestly, I’d rather lie back with my drink and watch the elephants, and again the reddening sky at dusk. Whatever the geological reasons are behind this amazing water world, I’ll take his word for it.

FRIDAY, DAY FIVE

Again, sadness, misery, as I prepare to leave camp. See and I walk on the raised boardwalk through the bush; my bag’s waiting in the game vehicle. I see a blur of brown and black about ten metres away.

‘Wild dogs!’ I say in a loud whisper. See isn’t convinced, but I am. I was surrounded by a pack of them once on an overland trip through Zambia.

We rush to the game vehicle, follow them; they stop briefly on the road. Their muzzles are bloodied. See radios his fellow rangers to alert them, and soon another vehicle joins us as we off road. The dogs soon disappear. But then there’s news of a lion kill somewhere, and we’re off in another direction.

‘Duck! Duck! Duck!’ See repeats. The bush is getting really thick; we’re driving over small trees. Bundu bashing. See tells me not to worry, that the trees getting flattened by the game vehicle pop back up, that the Land Cruiser has an underbelly designed to not destroy vegetation.

Then we come upon him – the male lion, tawny with a distended belly; he’s eaten his full and left the rest to his ladies. He’s blocking the track, though, the one open area to get closer to the kill, but we have to retreat, and try another route. See doesn’t see the huge log that soon obstructs us. He tries to drive over it, then reverse over it, gears grinding. Repeats several times. No luck. The lionesses are mostly hidden in the bush, lying in a circle and feasting on a wildebeest. About twenty metres away. Luckily fellow DumaTau guide TK and his guests are in the vehicle up ahead, and we summon him to help. He proves a superstar. This time my pulse accelerates but the lions couldn’t have cared less.

Free at last, See and I race to the airstrip – driving at maximum permissible speed, 40 km/hour, which feels fast on sand track. My adrenaline rises. Also because I know another goodbye is coming, another ‘handover’ – this time to whoever takes me under his wing at Vumbura Plains in the Okavango.

Luckily the plane is late, as we are; our arrivals coincide. I have just a few minutes to greet Keith again (he’s dropping off some guests I met in Maun), take a photo of him and See, and say whatever parting words I can manage to See.

Other than ‘thanks a million, it was incredible’, all I can think of saying is that I will do everything in my power to come back. See says he’ll be waiting.

As we take off and head south to the Delta, in the row of guides and game vehicles ready to take the next fortunate guests on safari, he’s the one waving.

Photographed by Melissa Siebert

Let’s plan your next journey

Ready?

When we say we’re there every step of the way, we mean it, literally. From planning the perfect circuit, to private inter-camp transfers on Wilderness Air, and easing you through Customs. We’re with you on the ground, at your side, 24-7, from start to finish. Ready to take the road less travelled? Contact our Travel Designers to plan an unforgettable journey.