Coupled with late rains, the arrival of the 2020 inundation brings some relief to northern Botswana, in the midst of the current turmoil of COVID-19 and the collapse in tourism-related industries around the globe.

Weather patterns and the resulting rainfall in south-central Africa are becoming more sporadic and erratic, resulting in droughts such as the one experienced in 2019. Despite this, we are happy to report that the waters are arriving in Botswana’s Okavango Delta, breathing life back into the system. Levels are starting to rise at our Vumbura camps, and together with the late rains the trees are now green, the pans are full and life is plentiful.

Storm clouds roll in over Vumbura Plains, bringing some much-needed rain to the region. Photo by Wilderness Safaris Ecologist Rob Taylor

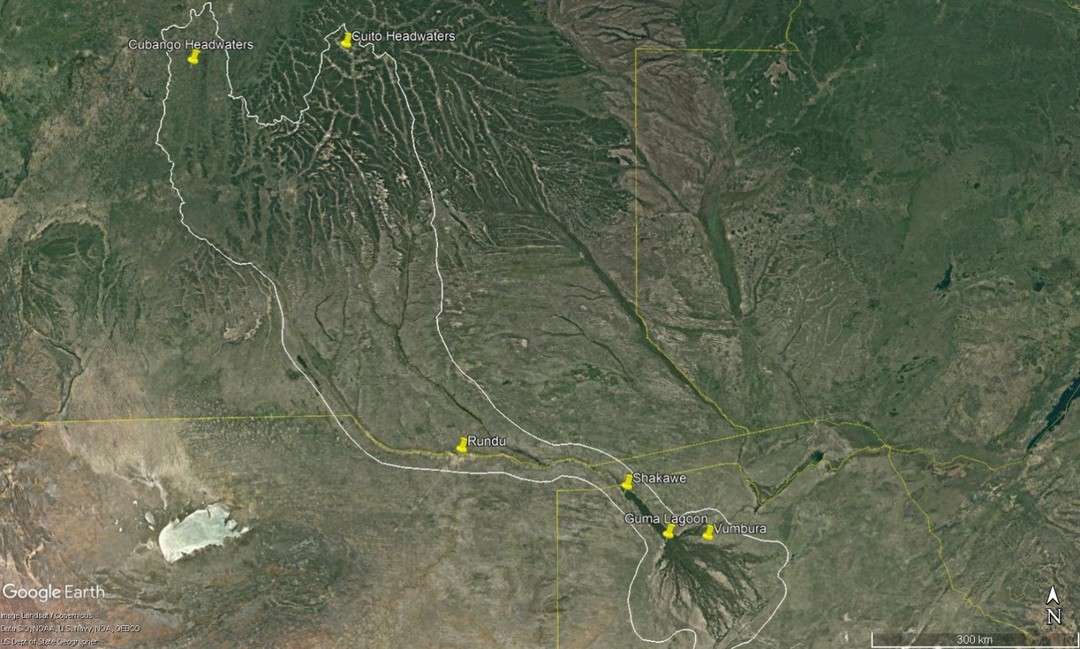

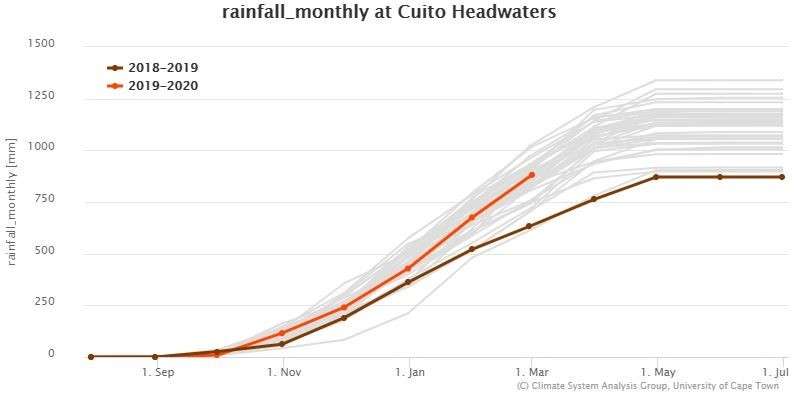

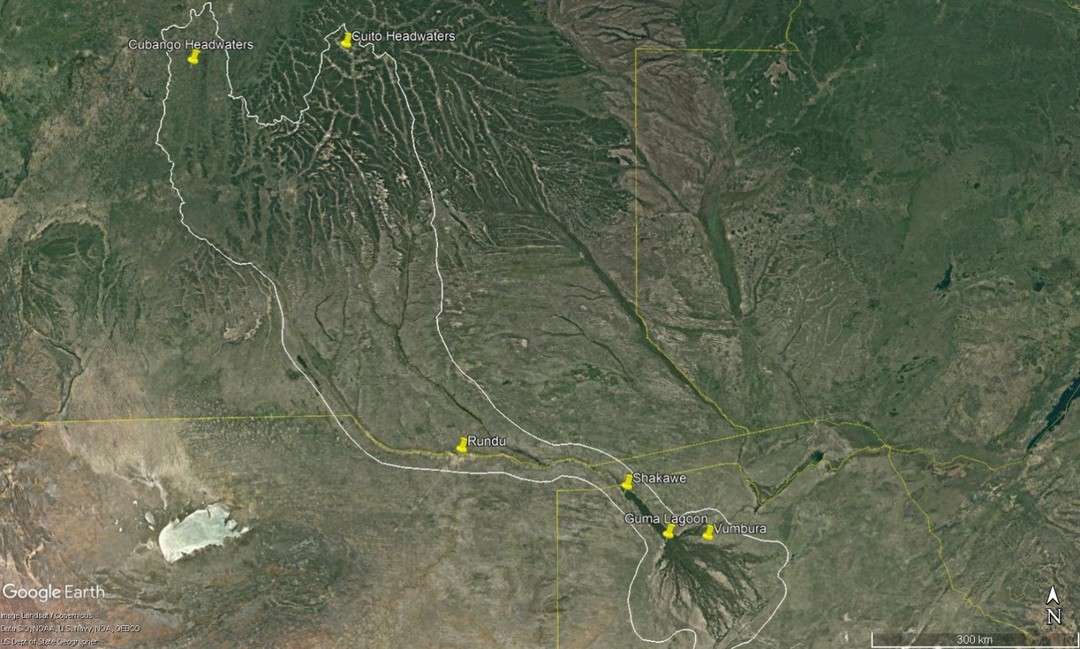

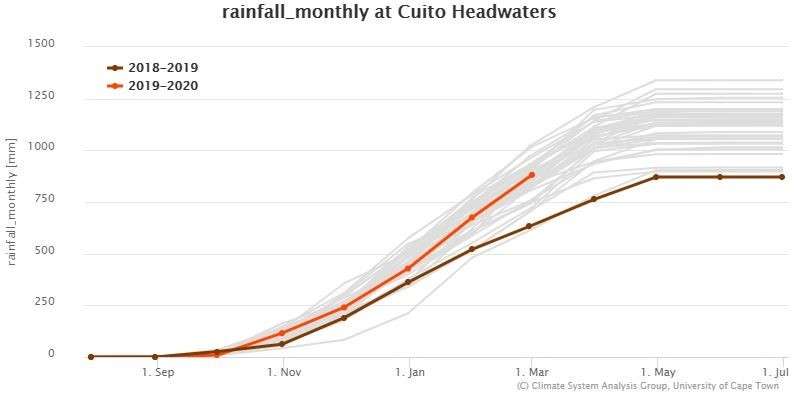

The process started seven months ago in September 2019 with the start of the rainy season in the highlands of Angola, from where the Okavango Delta sources its life-giving waters. Satellite rainfall data for the catchment shows that average to above average rainfall has fallen in the highlands over this season. The Cuito and Cubango rivers, the two main tributaries feeding the Kavango River, transfer rain water first through peat wetlands and source lakes and then through narrow steams, and rivers, until it arrives in Namibia and Botswana several months later.

The catchment of the Okavango River from the Cuito and Cubango tributaries in the highlands of Angola, through Namibia and down to the alluvial fan of the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Accumulated rainfall starting from August, for each year from 1981 for the Cubango (top) and Cuito headwaters (bottom) in Angola. The current rainfall season is indicated in red while the 2018/19 rainfall season is indicated in brown. Data is derived from satellite rainfall data graphed on the interactive website: cip.csag.uct.ac.za/monitoring/okavango/

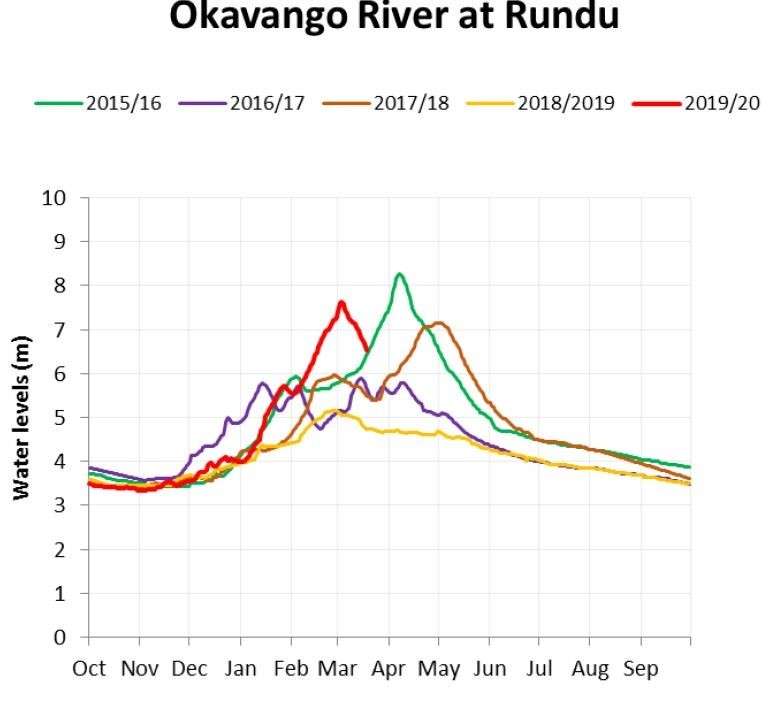

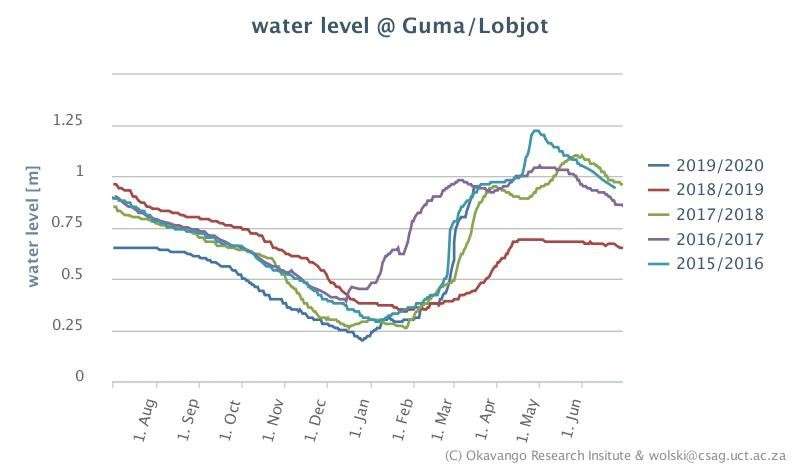

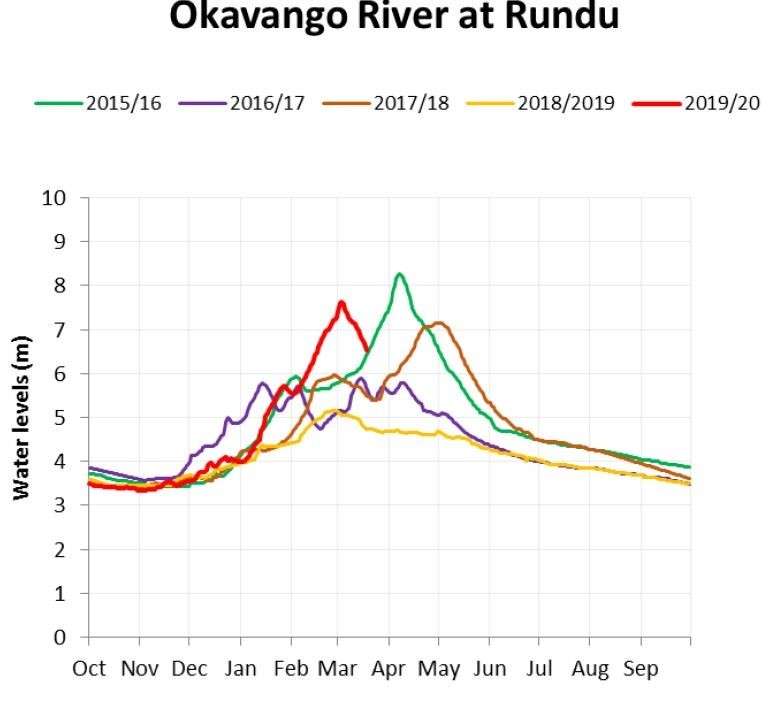

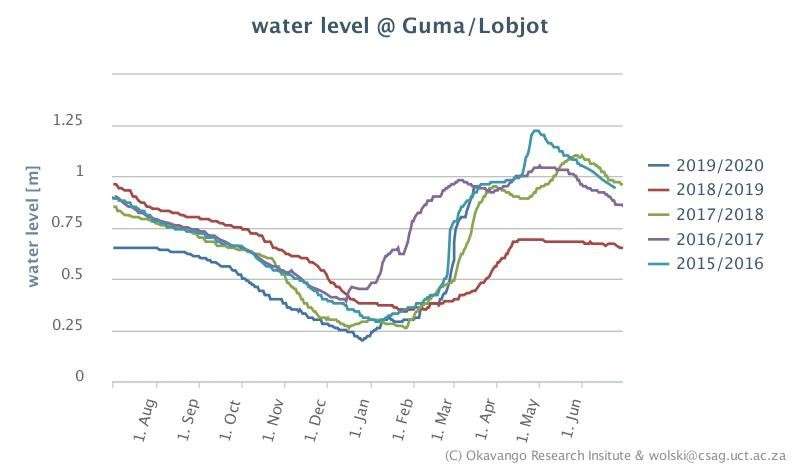

The flood reached its peak at Rundu in Namibia at the beginning of March 2020 and the waters have already begun to subside. Subsequently we have received reports from Shakawe in northern Botswana that the river has burst its banks and inundated vast areas of floodplain. As the river widens the amplitude of the flood decreases from a rise in ~4m at Rundu down to a rise of only ~1m at Guma Lagoon where it enters the alluvial fan of the Okavango Delta.

Over the past few weeks the waters have begun to rise at our Vumbura camps in the heart of the Okavango Delta.

The hydrographs showing the annual floods from the Okavango River at Rundu (top) and at Guma Lagoon (bottom) since the 2015/16 flood season. Data is provided from the National Hydrological Services, Flood Bulletin, Namibia and the Okavango Research Institute Monitoring website (www.okavangdata.ub.bw/ori), collected and submitted by Guy Lobjoit at Guma Lagoon Camp.

The average to above average rainfall in the upper catchment in Angola has transitioned into the neat flood peak in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. What does this mean for the region’s communities, wildlife and tourism?

Community-owned livestock can drink, ground water is replenished, refilling water wells, and water is made available to subsistence and small commercial agriculture.

With the arrival of the floods the fish start to breed in the shallow flood waters. Warm, shallow waters and the access to nutrients allow life to flourish. Wetland vegetation grows and many animals begin to concentrate in the vast floodplains.

Tourism is the backbone of the region’s economy and this unique annual flood event passing through one of Africa’s largest pristine natural areas separates this region from Africa’s many other superb natural offerings.

A bushveld rainfrog (Breviceps adspersus) emerges from the soil – where it hides during the dry months - to feed and find a mate after a downpour at Vumbura Plains. Photo by Wilderness Safaris Ecologist Rob Taylor.